In early 2023, I made the decision to begin writing and developing my own games. This is something I’ve wanted to do for many years, and life circumstances this year were finally right. The game industry remains competitive as always, and while attaining a job at a game studio remains a huge goal of mine, opportunities in Australia, and especially Western Australia, where I’m based, are rare.

Making my own games achieves three things:

- It results in portfolio pieces that I can use to aid my future employment prospects;

- It gives me practice at the actual nitty-gritty detail of game development, increasing my familiarity with the tools and processes involved, and my understanding of the obstacles unique to game dev; and most importantly,

- It allows me the opportunity to express myself creatively, and bring the stories in my head to life on my own terms.

In 2023 I pursued three different aspects of game development: making and releasing my first game, studying game design at a tertiary level, and attending my first game developer conference, GCAP. The rest of this post will focus on what I learned from each of these endeavours.

Making and Releasing a Game

In the first half of the year, I was solely focused on making and releasing The Symbol, which is a text-based narrative game that came in at a word count of roughly 30,000 words. I spent February mostly ideating and getting the large-scale pieces of the story straight in my head, and then actual writing and implementation took just over 3 months, from March to July.

Development Constraints

3 months is a short development time for a game, and, well, The Symbol is a short game (it can easily be played in a single sitting). I made several decisions which let me successfully constrain development time, as I’m wary of overcommitting to ambitious projects that drag on for many months or even years.

The first such decision was making the game text-based. I’m a writer at heart, and I’m primarily interested in telling stories through games (more on this later). The text-based format allowed me to forgo any reliance on artists or other people to add visuals to the game. I could add all the visuals myself through the writing, and leverage the ultimate graphics engine: the player’s imagination. Making it text-based meant that “development” largely consisted of what I can already do and already love doing: writing.

The second constraint was more external: I enrolled in tertiary study of game design and creative writing that was due to start in July, and so I knew I had to get the game done before then, as I wasn’t going to have the time to manage both things at once. This deadline really helped motivate me towards the end of the project.

Thirdly, while this was less of a conscious decision and more of a happy coincidence, the story of The Symbol is one that has been kicking around in my head for years. The Symbol explores two key concepts: a suicidal god, and an inversion of the god-disciple relationship. This results in a highly interesting situation where you, as the disciple, hold power over the Symbol, who wishes to die, and the Symbol must become your supplicant in the attempt to get what it wants.

Having all of this key underlying material meant the ideation phase was very short, as most of the framework and key themes were there. This helped me accurately plan and stick to a timeline, as ideation can otherwise be very open-ended as the writer explores broadly until they find the driving factors behind the story.

The Twine Engine

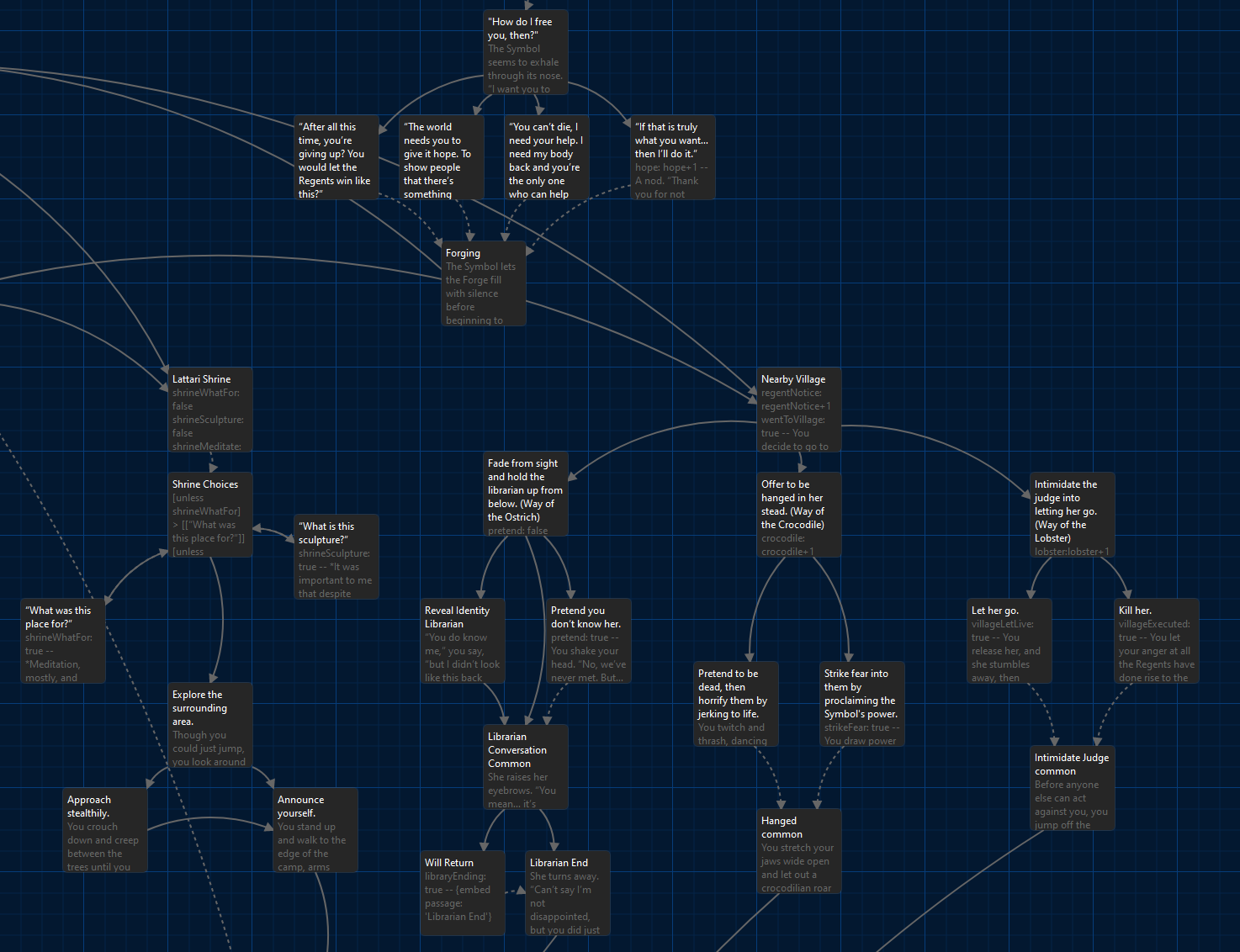

I used Twine as the engine for The Symbol, as it’s perfectly suited to the type of game I was making. I found the engine very simple to use, as it consists of making nodes of text (with an optional variables section) and linking them to each other. Here’s an example of what it looks like:

It’s worth noting that I actually wrote most of the game in a word processor, and then transferred the narrative into Twine once I had most of it together. This decision had pros and cons: writing in a word processor makes it far easier for me to get in the zone. In the Twine view, the actual text entry area is a small part on the side of the screen, and having to write the whole thing in that view would have been distracting and annoying.

The flipside of this decision was that after the fun “writing” phase was done, the “implementation” phase began where I spent a lot of time copypasting text into nodes, linking nodes together, and setting up variables to keep track of player decisions. The decision to write in a word processor meant these two phases were almost entirely separate, whereas if I’d written in Twine itself, they would have blurred together a bit more.

I’m not sure what I’ll do next time round yet, but I think writing in a word processor was the right way to go for my first time using Twine, as it prevented any implementation issues from derailing me from writing. There’s a good chance my next game won’t use Twine, so I may sidestep this conundrum entirely.

One last note on Twine: the node-based view in the screenshot above was intuitive, but became cumbersome as the number of nodes increased. Twine doesn’t offer a way to “condense” sections of nodes down, you just have to arrange them by clicking and dragging. Still, as a very lightweight engine, it did exactly what I needed it to. I kept the development effort minimal by not messing around with CSS or anything fancy, and just used the default settings. My software development experience came through in this project: I was very much striving for the smallest thing I could make that was still a game, and that primarily utilised my writing skills.

Interactivity and Branching

I learned first hand that compared to writing linear stories, even stories with a little bit of branching can quickly grow exponentially in terms of complexity. The Symbol is pretty low in terms of actual branching, but keeping track of player dialogue and interactions and ensuring that those were reflected going forward was more effort than I predicted, and I’m lucky that I kept the initial scope of the game small, otherwise I would have had to cut stuff once I approached my self-set deadline.

Overall, I finished The Symbol with a combination of relief and satisfaction. It felt like a strong step in the right direction, and it affirmed for me that just making the games I wanted to make was the surest way to achieve my game development goals.

By the way, if you’d like to play The Symbol, you can find it here. It plays in the browser, so no download required, and it’s free!

Studying Game Design at Uni

Practically the week after I finished The Symbol, the study period I was enrolled in started. I had enrolled in two individual units through Open Universities Australia, as I’ve learned from my uni explorations over the last few years that degrees take too long and at this point in time I learn far better by diving in and getting my hands dirty than by studying.

Nevertheless, I wanted to see what formally studying game design would yield, and unfortunately I was disappointed. The content was light-on and lacked rigour, and it felt more like a guided opportunity to develop game design documents and get feedback rather than actually learning the underlying rules of game design. I’ve learned far more about planning and executing projects through my software career, so it’s possible I’m not the target audience for an introductory game design unit. That said, I did learn a bit about the phases of game production, and about considerations that should go into designing a game.

I came out of that period of study in September wishing I’d spent those 3 months making another game instead! But, negative data is still data, and I know now that I’m not suited to the type of study that was offered in that unit.

Attending GCAP

In October, I attended Melbourne International Games Week, which began with the GCAP conference. Three days of attending talks and panels and meeting with new people left me exhausted, but it was a good insight into what goes on in the Australian game industry.

All the talks I attended were extremely good. I ended up following the Narrative talk track most of the time, to no one’s surprise. Highlights included Pacing in Narrative Games, a talk by Mads Mackenzie, the developer of Drăculești, and Lower Your Character Limit: Getting Bigger Laughs with Fewer Words, a talk on humour and comedy by Bones Draqul Hillier, a narrative designer at Mighty Kingdom that works on Star Trek: Lower Decks. These people were inspirational to hear speak, and I learned a lot from getting diverse perspectives on many aspects of game development, not just the writing side.

Just going for the educational aspect of the conference was valuable, and would have been worth the expense by itself. However, I also pursued networking opportunities while I was there, and learned a lot from this experience as well.

GCAP had set up MeetToMatch, a platform where you could book one-on-one meetings with people, and as someone who struggles socially with making small talk and making new connections, this was really helpful, as I could go into a meeting knowing who I was speaking with and why. I definitely flubbed a few of these meetings, as I struggled to find things to talk about or keep conversations going. I learned that networking is hard. I have never been a person that enjoys striking up conversations with strangers, but that’s exactly what you have to do to network. More than learning any technical skill, this is going to be the most difficult part of being involved in the game industry for me, because the networking side is more important than I gave it credit for. I had the chance to catch up with Anthony Sweet, a game designer that I already knew from Perth, and he told me that when people look for new hires, they want someone that they know they can get along with and work with for 8 hours a day, and those conversations happen in places like GCAP, not at the interview table. It seems I need to lean into this in order to make my dreams of working at a game studio a reality, so that was a powerful lesson to take away for next year.

I’ll finish up this section by sharing the highlight and lowlight of my networking experience at GCAP. The lowlight was for sure the Australian Game Developer Awards, because in addition to the social constraints of networking, it all took place in a packed venue with music so loud you had to yell to be heard, and everyone speaking over each other trying to be understood. Anyone who’s heard me speak knows that I have a quiet voice, and trying to raise it for extended periods of time is really hard for me. The AGDAs are probably the sort of thing that is more enjoyable if you know people already, and can just attach yourself to someone and follow them around (at least for an introvert like me).

The highlight, however, consisted of two conversations I had at the conference itself: one with Anthony, as I mentioned before, because he gave me some really good advice and is generally an extremely welcoming and friendly person, and the other was the opportunity to meet with Samantha Cable, Head of Narrative at Spoonful of Wonder, who are currently working on Copycat. I think everyone will agree that we need more cat-based games in the world, and talking to Sam about Copycat was an extremely enjoyable experience. She was really approachable and expressed interest in hearing about my projects too, so that was a fun, two-sided conversation.

I would say my overall impressions of GCAP were mixed, but I hope to attend it, or an event like it, again next year.

Next Steps

So, with all that learned, and 2023 approaching its end, my next steps are:

Remain Open to Opportunities

Since the industry is so competitive, it always helps to have the resume primed and ready to apply to job postings that come up. This is a bit of a lottery, but I’m standing by and ready to pounce should something emerge.

Network Locally

Perth has a game dev community, and I’m already a little bit involved, mostly by lurking on the Let’s Make Games discord. I’m going to make an effort to attend more game dev meetups and get to know some of the other game devs in Perth.

Make Another Game

The obvious answer, and the most important one. Another portfolio piece will help with job applications, and I can take the lessons I learned from The Symbol and make something slightly more ambitious. I’m currently experimenting with a variety of things, from an eldritch space simulator to a Cthulhupocalypse visual novel, and hope to have my direction solidified by the end of the year. I know for sure that I still want it to be primarily a narrative-driven effort, but as to exact story and genre, that’s up in the air.

Conclusion

It’s been a big year of learning for me. Making it in the game industry often feels like an asymptote, in that no matter how close you approach, the target is always that little bit further away. Nevertheless, there’s no denying I’ve made strides this year: actually making a game, exploring formal study options, and diving into the industry through a big conference.

I’m on the right track. All I can do is keep following my passion for telling stories and remain open to what comes my way.